Don Cusic, Andrew Smith, Mickie Akenson, James Akenson

Managing Editor’s Note:

Once again Andrew Smith in Tasmania, Australia provides a fascinating discussion of an important Country Music topic. A description of the John Edward collection at the University of North Carolina may be found at https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/20001/ . It is particularly interesting how some international persons become fascinated by U.S. based Country Music and other roots music forms. Andrew Smith not only knows Australian Country Music, but can link it to U.S. Country Music. This will be evident with the publication of Smith’s Tex Morton biography of later in Spring 2023 by the University of Tennessee Press.

The John Edwards connection also extends to the International Country Music Conference in a variety of ways. Edwards was mentioned by Andrew Smith at the 2018 International Country Music Conference in his keynote presentation on Australian Country Music. Smith also references Nolan Porterfield’s writing about John Edwards. Porterfield regularly presented and served as a panelist at ICMC up until his death. Finally, it is interesting how Smith identifies John Edwards dislike for the emerging Country Music of the 1950s. The disdain for contemporary Country Music certainly wasn’t unique to Edwards.

The 1980 Storm Over Nashville book by Everett Corbin shows that lovers of ‘pure,’ traditional Country Music have found lots to dislike for quite some time. This dislike for contemporary Country Music continues as a theme into the third decade of the 21st century with particular dislike for the Bro Country associated with the likes of the now fading Florida Georgia Line. Edwards would likely be appalled by the Wall of Sound production values that make much of contemporary Country Music sound rock-like and make lyrics harder and harder to understand.

The name “John Edwards” is perhaps better known within country music circles in the United States than in Australia, even though Edwards was an Australian who never left the shores of his own country. During the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, Edwards collected “hillbilly” and old-time country music, researched the genre, wrote about the music in small newsletters and magazines like Country & Western Spotlight, and compiled ground-breaking discographies of pivotal country music artists. His legacy, however, is not within the country of his birth, but in the United States instead.

John Kenneth Fielder Edwards was born in Sydney on 22 July 1932, and from the beginning displayed considerable academic promise. In his last year at school he became enthralled with American country music and collected as many discs of it as he could, initially from junk shops and radio stations, and later from other collectors in Australia and overseas. By late 1959, he estimated he had acquired some twoandahalfthousand discs, including a complete set of Jimmie Rodgers’ 78s, nearly all the Carter Family’s output (around three hundred titles in all), and about one hundred openreel tapes which, he projected, amounted to another thousand discs.

He listed his favourite artists as including Gid Tanner, Clayton McMichen, Buell Kazee, Bradley Kincaid, Charlie Poole, Ernest Stoneman, Kelly Harrell and Goebel Reeves;1 but apart from Tex Morton and the Hawking Brothers (Russell and Alan), he had scant regard for Australian artists, and certainly resented the emergence of electrified country music and the development of the honky tonk genre during the 1950s in the United States, dismissively describing it as “slicked-up, popstyle” music with “jivey, electrified, drugstore crooning”.2

Edwards was especially fascinated by country music of the 1920s and early 1930s—a “golden age”, as he called it. He regarded the music of that era as folk music, relatively untainted by commercial influences (though the music was evolving all the time). It’s conceivable that, in his early phase of collecting at least, Edwards’ knowledge of American country music was somewhat skewed by what had been issued in Australia during “the golden age”: mainly “citybilly” artists like Vernon Dalhart, Carson Robison and Frankie Marvin, though Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, Hank Snow and Wilf Carter were released locally during the 1930s and 1940s. Virtually nothing by Ernest Stoneman, Charlie Poole or similar artists, however, was released in Australia during that time.

Edwards was especially fascinated by country music of the 1920s and early 1930s—a “golden age”, as he called it. He regarded the music of that era as folk music, relatively untainted by commercial influences (though the music was evolving all the time). It’s conceivable that, in his early phase of collecting at least, Edwards’ knowledge of American country music was somewhat skewed by what had been issued in Australia during “the golden age”: mainly “citybilly” artists like Vernon Dalhart, Carson Robison and Frankie Marvin, though Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, Hank Snow and Wilf Carter were released locally during the 1930s and 1940s. Virtually nothing by Ernest Stoneman, Charlie Poole or similar artists, however, was released in Australia during that time.

Edwards was much more than a collector, however. He compiled one of the first discographies of Jimmie Rodgers which “for more than a decade … remained the definitive Rodgers discography” according to Nolan Porterfield, Jimmie Rodgers’ biographer.3 He also produced the first Tex Morton discography during the 1950s.

Working from Sydney with just a typewriter and telephone, he corresponded with several early American hillbilly artists whose locations were unknown at the time to researchers in the United States, all the while acquiring firsthand information about the history of country music. He located Goebel Reeves, Buell Kazee, Gid Tanner, Cliff Carlisle and Dorsey Dixon, for example—impressive feats given that he was based in Sydney in preinternet days. He most likely found their addresses from record companies which sent royalty payments to them.

Sara Carter referred to him as “Our John in Australia”. He wrote to Dorsey Dixon and the two struck up a friendship through correspondence. When Dixon learnt of his Australian friend’s death, he wrote and recorded (privately) a tribute song to Edwards and sent it to Edwards’ mother. Edwards also exchanged information and swapped records with collectors of early country music in England (an early contact there was George Tye) and the United States (including Jim Evans, president of the Jimmie Rodgers Fan Club in Lubbock, Texas).

Edwards ultimately planned to relocate to the United States and study folklore, but his life was cut short by a fatal road accident on Christmas Eve 1960. Edwards left his entire collection and research material to likeminded folk in the United States, including folklorists D.K. Wilgus, Archie Green and John Greenway and collectors like Eugene Earle. Nolan Porterfield, however, wrote that initially the United States Customs Department slapped a duty on the importing of Edwards’ collection, prompting the Los Angeles Times to write: “Only the United States would levy a tax on a priceless chunk of its own culture”.4

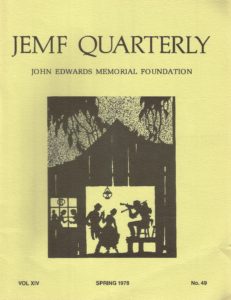

Edwards’ friends established the John Edwards Memorial Foundation (JEMF) which was originally located at the University of California in Los Angeles. The JEMF was one of the first “serious” archives of country music although its importance decreased with the inception of the Country Music Foundation (CMF) in Nashville in 1964 and the CMF Library in 1968.

The collection is currently housed (in excellent hands) at the Wilson Library, and is part of the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For some years, the JEMF published a “serious” magazine called the JEMF Quarterly (JEMFQ); and in 2002 the John Edwards Memorial Forum offered the Southern Folklore Collection “its last dollar” to fund a magnum opus, Country Music Sources: a Biblio-Discography of Commercially Recorded Traditional Music,5 which stands alongside Tony Russell’s indispensable country music discography on my bookshelf.

Edwards’ stipulations in his will that his records were “not to be given, sold, or made available to anyone outside the USA” was more than likely fuelled by an underlying bitterness that his own efforts hadn’t been recognised by Australian academics, though this isn’t surprising given that Australian universities commonly regarded country music as unworthy of serious study, unlike more enlightened institutions in the United States.6 In fact, Edwards’ resentment probably also extended more generally to many in the local music sphere as well.

Edwards’ influence, however, might have had some bearing on the creation of Australia’s National Film and Sound Archive (now ScreenSound). Researcher and discographer Peter Burgis wrote: “During the late 1960s I used the fate of the John Edward’s record collection as a reason to convince Mr (later Sir) Harold White, National Librarian of the National Library of Australia [NLA], of the need to establish a national collection of sound recordings.

Fortunately, Sir Harold was a visionary administrator who needed no convincing of the worthiness of the proposal. In the early 1970s he created a Sound Recording Section in the NLA to help ensure outstanding collections could be preserved in Australia. In the 1980s this collection became a major resource of a freshly founded National Film & Sound Archive”.

I was only seven years old when Edwards died, but I’ve listened to several of his round-robin tapes, in which likeminded collectors discussed music and recorded the odd song from their collection. Edwards comes across as a “purist” who had no time for contemporary country music of the 1950s (although he did seem to have a soft spot for Floyd Tillman).

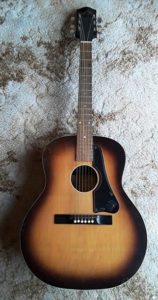

He even idolised some artists: why would anyone bother to record a Carter Family song, he pondered (chastising the collector who had sent such a recording), when the Carters were perfection themselves? People who knew him spoke of his almostfanatical care with handling and playing his precious seventy-eight records, and how he insisted on using a special stylus to minimise surface wear-and-tear; and he was more than a passable guitarist and singer, as a compilation of his private recordings amply demonstrates.

John Edwards’ acoustic Maton guitar, however, is now in Australia. Some twenty years ago, I received a letter from Australian customs stating that I owed over four hundred dollars import duty on the guitar, which was sent to me by a fellow collector in Los Angeles. He was a friend of Eugene Earle’s, one of Edwards’ American contacts and a collector of note, who had given the guitar to my friend, who in turn thought it should be returned to Australia.

Fortunately, I managed to haggle the import duty down to about two hundred dollars. I intended to give it to a member of Edwards’ family, but Edwards has no traceable relatives still alive in Australia; and an Australian archive of country music was somewhat inquisitive as to the importance of Edwards to country music research. In any case, Edwards, I hope, would be more than content that—thanks to like-minded Americans—his collection resides in good hands in the United States.

Footnotes

- Edwards, J. “Noted Country Collectors”, Country Directory no 1, November 1960. p 8

- Edwards, J. 1956 “What’s Wrong With Local Country Music?” Reprinted in Country & Western Spotlight special edition reprinted in Country & Western Spotlight Special Edition, tribute to John Edwards. p 32

- Porterfield, N. 1979. Jimmie Rodgers. Champaigne, Illinois: The University of Illinois Press. p 386

- Porterfield, N. “John Edwards: Pioneering Country Music Scholar”, Roots & Crossovers: Australian Country Music Volume 2. Gympie: aicmPress. p 58

- Porterfield, N. “John Edwards: Pioneering Country Music Scholar”, Roots & Crossovers: Australian Country Music Volume 2. Gympie: aicmPress. p 65

- Hirsch, S. “Collector Extraordinaire”, Journal of Country Music, vol 13 no 2, 1990. pp 27-28. Useful articles on Edwards, besides Hirsch’s piece, include Jazzer Smith’s “The Long Journey Home” (The Book of Australian Country Music, pp 60-71) and Nolan Porterfield’s “John Edwards: Pioneering Country Music Scholar” (Roots and Crossovers, pp 55-66).